Listen to James Piercy talk with Jesús, a member of our Public Oversight Committee, who suffered from a traumatic brain injury over 7 years ago.

Jesús talks about his brain injury and how it changed his life. From a documentary maker, working with people all over the world, to someone who is documenting their recovery journey, working with his dedicated team of clinicians and therapists, Jesús explains how much his life has changed. He has been supported by Keeley Bullock at Swim for Tri, who has helped him get back in the water, and Dr. Theo Farley, a sports concussion therapist, who has supported his physiotherapy. Jesús also talks about the importance that new technologies have played in his recovery and how important it is to keep supporting their development.

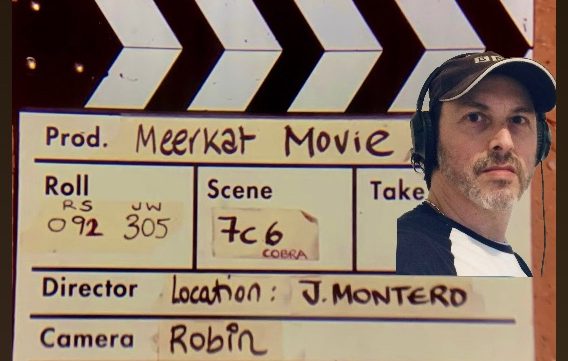

| James (0:08) | Welcome to another podcast from the HealthTech Research Centre in Brain and Spinal Injury. We're talking to some researchers, some innovators, and importantly, we're talking to some patients and carers as well. And with me today, I have Jesús Montero, who is a member of the Public Oversight Committee for the HealthTech Research Centre.

Good morning. It's really nice of you to join the call. How are you today? |

| Jesús (0:34) | Well, thank you so much, James. It's actually the first time that I am speaking about my traumatic brain injury publicly. So thank you so much, James, for having me. |

| James (0:46) | Well, thanks for coming along and sharing your story. So, well, let's start with that story, shall we? You said you had a traumatic brain injury. When did that happen? |

| Jesús (0:56) | That happened in March 2017. |

| James (0:59) | Okay, so about seven years ago now. And how did it happen? Was it a car accident? You fell over? |

| Jesús (1:07) | Well, mine is a very peculiar, freak accident that happened, you know. I'm a filmmaker and I've travelled all over the world, you know, and many a time I've risked my life and nothing ever happened to me.

So my accident puts life into perspective because one day I came back from a trip, a business trip to Norway to my job with National Geographic, and I went for a dip, you know, a swim in a public pool in London, a place where you're supposed to feel safe and protected. And, it's quite unbelievable, because I don't think many people on this planet can actually say that a lifeguard nearly killed me. It was negligence, you know, so it was the lifeguard who caused my traumatic brain injury. You know, for somebody who's been in conflict zones, jungle, deserts, you know, to be on home turf and experienced something that changed, ruined is the word, my life. So it puts life into perspective that we have to live life every day because we just don't know what's around the corner. |

| James (2:13) | Absolutely. And things can just sort of change like that, can't they? So I don't want to spend ages talking about your injury, but just so that the listeners can get a kind of an idea of what happened. So you've banged your head in a pool. So presumably you need to get taken there and you're rushed, what, to the nearest hospital? |

| Jesús (2:29) | Yeah, well, it's the classic acute phase of a traumatic brain injury. Because the first 48 hours, we know that they are crucial. But the aftermath of the injury, it was during those initial 48 hours that we realised what actually had happened.

So it was several trips to A&E until I eventually got the diagnosis of traumatic brain injury. And this is when I realised that, you know, I couldn't hold my toothbrush, you know, I was dropping teaspoons, I lost all my spatial awareness. It was that tsunami of, you know, events that follow some traumatic brain injuries. |

| James (3:10) | Yeah, I'm interested in that story. You said you made several trips. So the first time you went to hospital, what did they do? They just sort of sent you home again? Did they give you a scan? |

| Jesús (3:19) | If I have to be brutally honest, you know, I've been surrounded by the best medical team, you know, of consultants in the UK, some of the best in the world. But unfortunately, the first neurologist that saw me during the first A&E, she wasn't very good. Initially, you know, I should have had a scan straight away because then those 48 hours, you know, highlighted that there was something seriously wrong with me.

And for somebody who works in, you know, making science programmes, you know, now, I just, if I look back at that day, I say, oh my God, how on earth, you know, they let me go, walk away, to come back when things got really, really bad. |

| James (4:06) | Yeah, and when things progressed. So you've touched on a few things of your life before your injury there. And I want to sort of unpick that a bit, because it sounds like you had an amazing career travelling the world. And you said you're a filmmaker. So what kind of films were you producing? |

| Jesús (4:19) | It was wonderful to have that kind of, you know, experience before the injury, where I could see, you know, the world. And, you know, it was a privilege for me to work with incredible companies and be exposed to different cultures, you know

Every time you do a film, you do a proper risk assessment. So for me, it's really frustrating to see that my brain injury was caused, you know, in a place where you're supposed to be safe and protected. |

| James (4:50) | We'll put a link to some of your previous work under this podcast. So do check some of that stuff. Amazing things. |

| Jesús (4:58) | It's also linked to why I decided to join, you know, the POC, because I think as a filmmaker, you know, research always came naturally to me. It's part of my professional DNA, to be inquisitive, you know, investigative. And eventually, you know, you share the results with an audience. So, you don't get to do more than 100 air crash investigations for National Geographic if you don't have that kind of inquisitive mind.

So after my TBI, luckily, this was one of the few things that did not change, you know, this curious mind of mine. And because of my complex recovery trajectory, I kind of wanted to find a platform to share my experience, you know, the good and the bad, you know, in the hope that my recovery experience from this devastating and invisible type of injury could help future generations of acquired brain injury survivors. |

| James (6:00) | I'm trying to get my head around your story. So you've gone to A&E, they've sort of sent you away, you'll be all right, there's nothing wrong, keep an eye, you go back, you get a scan, and clearly you're having some quite dramatic symptoms. (Jesús: Yes) Then I guess everything starts to unravel. You can't just go back to your job. |

| Jesús (6:16) | Absolutely. And I think the problem is, it was when I looked in the mirror, and I could no longer recognize what my brain and my body could not do, you know, and, and we forget that we were all diamonds, you know what I mean? And, you know, when I look in the mirror, I could see that that diamond that used to be shining bright, and was not shining anymore.

And I always say that every diamond needs a cutter, you know what I mean? And, and the moment that I got together with an incredible group of consultants and specialists, my cutters, you know, little by little, we went through the layers of damage that happened to me. And like diamond cutters, you know, a diamond has got 58 facets. And I think the recovery from a brain injury is as complex as that, you know, you need a good team of consultants, you know, for that diamond to to shine again. So when I got the diagnosis, from one of the best in the land, you know, Professor David Sharp, that's exactly when I knew that we had a roadmap that is going to take a long time, because people don't know that recovery from a brain injury is not measured in weeks or months, you know, recovery from a brain injury, sadly, is measured in years. |

| James (7:47) | Absolutely. Yeah. And we know that we need to have this multidisciplinary approach. And I like your idea of the different facets. And we can't just polish one face of a diamond, right? We need to get the whole thing to come together. |

| Jesús (8:00) | Well, speaking about that, you know, it is just crucial, because as I say, you are in the hands of people who are talking to you about, you know, in a very difficult jargon, because you have to get inside your head. And in my case, you know, I was suffering from ataxia, I lost vision in my right eye, I lost hearing in the right ear, you know, my musculoskeletal structure was very damaged, you know, my place cells, you know, were fried, my hippocampus, you know, what I call our GPS went out of the window, I had absolutely no spatial awareness.

And somebody who's travelled the world and would be comfortable, you know, if you drop me anywhere on the planet, all of a sudden, I was not able even to navigate in my room or outside. So going back to the simile of the diamond, you know, we had to rewire me like a robot, every single bit of my body, my brain, you know, through complex technology. |

| James (9:06) | And you mentioned the word sort of invisible injury earlier on, and you look, if I can use the word, you look completely normal, it looks like there's nothing wrong with you at all. You look fit and healthy. And there's those unseen difficulties. |

| Jesús (9:24) | Yeah, it's really funny. I remember when I was discussing because they knew my consultants knew exactly the kind of person that they had in front of them, you know, I was somebody who could work 14 hours a day on location for three months, seven days a week, you know, so I was indefatigable. And, and I was so frustrated, even today, you know, I'm still, you know, I still have many cognitive impairments. And, but as you say, if you look at me this, you say, well, there's nothing wrong with the guy.

But I remember that my consultants, you know, said, “well, Jesús, the thing is, that before your injury, you were a Ferrari, you know, and the problem is that after your TBI, you lost your four wheels. And what we're doing is trying to get those four wheels back on one at a time. And until we managed to get the four wheels on, you won't be able to function properly, you won't be able to get back on that roadmap to return eventually to work and realise what your life is going to be after your injury.” |

| James (10:32) | Yeah. And I what I found after my brain injury was just enormous frustration, things that I could remember doing, and that were really easy to do. And now we're just enormously difficult and took so much longer.

And I guess in your case, it must be a similar thing. You're a highflyer, you're successful, and you know what you're capable of doing. And now suddenly, you just can't. |

| Jesús (10:57) | It's very frustrating. Many of us use a laptop, you know, and as long as the hard drive is working, the laptop can function. But if you damage the hard drive, when you look at the laptop, it still looks like a laptop, but you're not able to use any of it, you know. And I think that's what happens with a brain injury, you know, all of a sudden, you know, you just don't function, and you have to follow the advice of, of those experts.

And in my case, you know, I cannot really not mention the two people, you know, who actually helped me get through these, you know, recovery trajectory. And one of them is one of the best concussion specialists in the land, you know, Dr. Theo Farley, and he is the one who throughout, you know, these seven years of recovery, has actually made me understand what this brain injury is and how long it takes. And the second one is going back to Professor David Sharp. He, from the very beginning, he was very keen that I should get back in the water in the pool where I had my accident, you know. And of course, that didn't happen, you know, it took me a year, to be physically able to walk to the poolside and be able to actually get in the water. When I got to the pool for the first time, and that was in October 2018, with my incredible swimming coach, Keeley Bullock at Swim for Tri, who specializes in getting people with traumatic brain injuries back in the water. And it was the first time that I got in the pool with her, when I realized what had happened to my body. You know, it was the first time that I was completely clear about my ataxia, because the left side of my body, the blow was to the right side of the brain. So the left side of the body did not respond. And that only, you know, became obvious when I got back in the water. And I remember that day, that when I got in the water, and I realized what had happened to my body. Having been an avid swimmer, you know, I could swim two kilometers in 30 minutes, you know, up until the day where I had my accident, you know. But when I realized what happened, during those initial few seconds, being back in the water, I was about to break into tears and Keeley just stopped me and she said, “Let's get out of the water.” And she took me to the engine room, you know, the next to the poolside, you know, and, and there, I burst into tears, and I let it all out, you know, and then she looked at me, and she said, “Let's get back in the water now.” And we did. And it took us years of very demanding, basic, you know, rehabilitation in the water, for me to be able to swim again. The good news is that, you know, if you're resilient, and you surround yourself with the right team of people, as I go back to, you know, the diamond, you know, now I can swim, don't get me wrong, not symptom free, okay. But I can swim 700 meters in one session, with symptoms, but that, for me, and you know, my name is Jesús, it's pretty much a miracle, you know. |

| James (14:35) | Yeah, you touched on something really interesting there, you described quite movingly, what it was like the first time you got back in the pool. And I think there was a realization there about your identity changing. Because you used to be the guy who would go swim for kilometers on end, and now you were a different person in that moment. And I think for a lot of people who've had a brain injury, it's that challenge to your identity, and trying to find out who you are now, that is really, really difficult. |

| Jesús (15:04) | And I think that's why, you know, to have good consultants. People who are not just decisions or clinicians, people who have a clear understanding of how their brain works, you know.

And when it comes to Keeley, I wasn't the first brain injury survivor that, you know, she'd helped getting back in the water and swimming, it took us years, you know, of weekly sessions, you know, so. But it just shows you what the human body and the brain can do, you know, there's that concept of neuroplasticity. And if you have the will, you know, I think the brain finds a way. |

| James (15:50) | The HealthTech Research Center is about tech. And I wonder whether in your recovery, you've had any use of new kinds of technologies to support you, any sort of digital aids or physical bits of equipment that have helped you in your recovery? |

| Jesús (16:03) | Yes, yes. And that's why I think the kind of work that we do at the POC, the Public Oversight Committee is really important. Because in my case, you know, one of the most complex bits of technology, you know, that I had to use is something that was not offered, you know, by the NHS. But my consultants, you know, realized that there was a new bit of technology, you know, to do what's called proprioception therapy.

And that involves, because as I said before, I, you know, my place cells were completely fried, I lost my spatial awareness. So we have to spend years of really complex, you know, exercises using laser, a laser beam, you know, that I wore like a torch in my head, you know, and that allowed us, you know, through different bits of schemes on the wall and tracing, you know, the lines and starting from an X. And years later, being able to navigate with the laser through a labyrinth, you know, so you can see the progression. And those are exercises that you do gradually, first in sitting, then standing with your legs, you know, apart, then legs together. So there's, it took us years, you know, but as I said, because I'm, I'm a researcher, you know, I, we kept logs of absolutely the progression of that recovery trajectory, just to prove that this kind of technology helps, you know, and in my way, I lost vision in the right eye. And due to all this bulk of incredible work that took years, my vision got better. So, and that's something that my consultants told me at the beginning, but when they showed me this complex bit of technology, I couldn't quite understand, you know, how is this going to help repair my vision, you know. But then you understand about, you know, optical nerves, you know, blood pumping into your nerves and into your brain, and then everything fits into place. So that was one bit of, of technology that I was able to use funding it myself, you know, alongside with the, with the NHS. And the other one was to recover my hearing. So basically, what happened to me is that the amygdala, the amygdala is like a tiny almond shapeed bit of the brain that controls the flight and fight response. And because of the damage to my right ear, you know, there were certain frequencies that triggered a negative response on the amygdala. So basically, I would just get nauseous, sweaty palms, anxiety out of the blue. And for somebody who's worked in a television studio all his life, you know, where I have to listen to accidents, you know, sound effects and whatever, I said, my God, I just can't believe this is happening to me. So they explained, there was this thing called hearing therapy using a bit of kit called the Oticon. They are sound noise generators that you use, you know, again, it took months and months. By using this type of technology, in a way, we were able to recalibrate that negative response in the amygdala. And I'm no longer, you know, we've been able after a year and a half of this therapy, and this has been through the NHS, you know, so good news. So yeah, for anybody listening to this, you know, this type of therapy is available. So that's technology for you, you know. |

| James (20:00) | That sounds great. It sounds to me that one of the things that's helped your recovery is understanding what's happening. And that understanding that it's not a quick process. (Jesús: Yes, I think so)

Do you think that being able to track your improvement over time has helped you? Because I know it's really frustrating that it's so slow, this recovery, being able to see, look back and see where you've come from, rather than how far it is still to go. |

| Jesús (20:25) | Absolutely, absolutely. You know, and I think it also going back to what I'm doing with Public Oversight Committee, you know, you know, I've worked, I've done hundreds of programmes about air crash investigations. And, you know, my logs are just like an investigation into, you know, my TBI is like a plane crash.

And what we need to look is at the data. I'm on week 361 of my recovery now, and I'm still doing my logs. But that allows us, you know, to go back to the beginning of my journey and see everything, you know, daily that I've been able to do and how we can chart the decrease of symptomatology and the things that have repaired according to what we've used, you know. And the good thing about this is that when you do an air crash investigation, there's an official report, you know, and you look at the official report, and that basically tells you the best thing that you can do to prevent an accident, you know, so you can look at the data and feedback, you know, the things that you can do to make things better for other survivors. |

| James (21:34) | Yeah, absolutely. And let's hope that there's some learning that comes out of these experiences. And we really thank you for your time on the committee and helping us kind of steer and shape the direction of things, particularly about the patient and public involvement and getting, building that lived experience and getting patients to talk to researchers and innovators, develop these new technologies. (Jesús: Fantastic!)

Well, thank you ever so much for your time, Jesús. I really appreciate you sharing your story with us and good luck with your recovery. We hope to see you improving day on day and year on year to come. |

| Jesús (22:06) | It's been a pleasure. Thank you, James. |

More like this:

Charity Podcast – Sarah Green Headway

Listen to James Piercy talk with Sarah Green of Headway Cambridge and Peterborough. They discuss the work [...]

Patient Podcast – Steve Brown

T.V presenter and paralympian Steve Brown talks about his spinal injury and for ming a new identity [...]

Public involvement in research impact toolkit (PIRIT)

Free to download, PIRIT is a set of pragmatic tools which aim to support researchers working with [...]