Listen to James Piercy talk with Chloë Haywood, Executive Director of UKABIF Charity, and Jennifer Misak, Senior Economist, about the Cost of ABI report, published last month.

Chloë, Jennifer and James discuss the content of the report, what the different costs actually mean, and what they hope will be the government’s response to this report. They discuss how this is a development of the previously published Time for Change report, but it looks more specifically at the economic and welfare costs to the UK economy. You can read both reports by clicking the buttons below, or visit the UKABIF website for more updates on the progress of this report.

| James (0:08) | Welcome to another of these podcasts from the NIHR HealthTech Research Centre in Brain and Spinal Injury. And I'm really, really pleased to be joined by a couple of experts in this conversation. And first of all, I'd like to say a big hello to Chloë Hayward, who is Executive Director of the United Kingdom Acquired Brain Injury Forum. Hi, Chloë. Thanks for coming and joining in the chat. |

| Chloë (0:30) | Hi, James. How are you doing? |

| James (0:33) | Good. Thank you. So the reason I wanted to pull you in is that UKABIF have just published this report about the cost to the UK economy of acquired brain injury. So can you just give us an idea of why? Why would you do this piece of work? |

| Chloë (0:49) | Absolutely, thanks. So you may recall, or some of your listeners might recall, that back in 2018, UKABIF produced a different report, which we published on behalf of the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Acquired Brain Injury, which was called Acquired Brain Injury and Neurorehabilitation - Time for Change.So that's now coming on for, sort of, seven years old, and we really felt like we needed to update that. We'd been working on the basis of that being the cornerstone of the work that we were doing with the All-Party Parliamentary Group, but it was dated and there's been a lot of new evidence that's been published since then. So we wanted to really provide some sort of an update.

We obviously have a new government, and we have had to re-form the All-Party Parliamentary Group. So it really felt like an opportune moment with a new government to really refresh the evidence, and obviously, data is really key to any kind of decision making. So we wanted to produce a publication that was really focused on what we know about acquired brain injury. And so that's what motivated us to produce it. |

| James (1:56) | And the Time for Change report sort of had areas, if I remember correctly, where we ought to be focusing. So we ought to be thinking about education, we ought to be thinking about criminal justice and different sort of areas of government. And this report is kind of specifically focused on the costs.So is there a sort of a headline figure? How much does it cost the UK a year to care for people with acquired brain injuries? |

| Chloë (2:19) | You might recall that in the previous publication, we had used a figure that was produced in a report published by the Centre for Mental Health, which had estimated the cost of a traumatic brain injury per year to be £15 billion, which is a huge number. Obviously, the area that we work in is not just traumatic; it's acquired brain injury. So we really wanted to try and provide some sort of an update to that figure because we know how powerful it's been to use that. So really, that was the kind of the cornerstone that initiated this work was to really try and update that and then to extend that into looking in more detail at some of the breakdown of those costs and some other costs which we hadn't looked at all before, such as the wellbeing cost. |

| James (3:03) | Sure. OK, so here we are in 2025. What is the headline figure for the cost to the UK? |

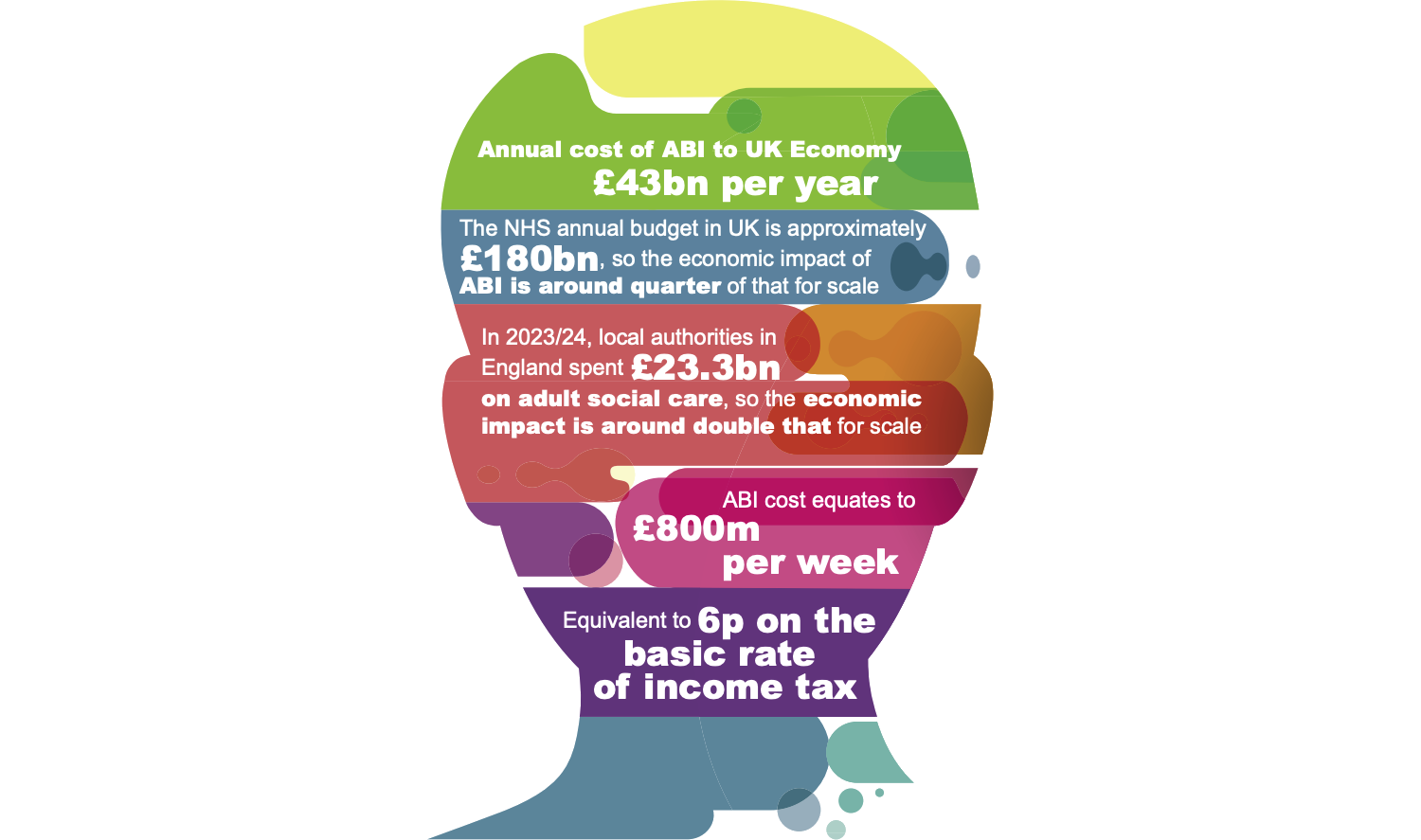

| Chloë (3:10) | So the headline figure, the cost to the UK of acquired brain injury, is £43 billion per year. |

| James (3:19) | I mean, that's just an astonishing number, isn't it? And I think that most people like me are now scratching their heads and trying to understand just what that means and how big a figure that is. What we really need is an economist to help us kind of understand what these costs mean and kind of where they come from. So it's fantastic that we're joined by Jennifer Misak, who's the economist who actually authored the report. Jennifer, thanks so much for joining us on the call. |

| Jennifer (3:43) | Thanks, James. Hi. |

| James (3:44) | So this figure of 43 billion quid, I'm struggling to understand what that means, because it's a phenomenal amount of money. How does that compare to other costs? For example, how much do we spend on the NHS as a whole? This is obviously one tiny part of those costs. |

| Jennifer (3:59) | Yes. So the annual budget to the NHS is around £180 billion a year. So it's about a quarter of the total spend on the NHS in a year. So it's a really, really significant amount. Something else you could compare it to, you know, it works out to be about £800 million a week, which feels pretty enormous as well. |

| James (4:23) | Yeah, that's colossal. £800 million. I mean, that's more than footballers earn, right? That's proper money. |

| Jennifer (4:29) | Exactly. More than several footballers. |

| James (4:32) | So I guess the obvious question next, then, is where does that figure come from? I presume there are some things you could literally look up the cost. How much does it cost for an ambulance to drive someone to hospital? So, where do you find that? Are those costs all published? |

| Jennifer (4:45) | So most of this data is published. The main set of data in terms of the numbers of people with acquired brain injury, and here we're looking at traumatic brain injury, stroke and brain tumour in particular. They're the kind of main areas we've got incidence data for. So that's the number of people appearing at hospital. And then we turn those hospital episode statistics into actual people. And then from there, we use the various different costs in terms of NHS costs. So that spells in hospital. We also have things like the cost of those people not working. So the lost productivity to the economy of durations. Obviously, we have to assume some of this isn't available. So we have to assume how long people are out of work for their return to work, etc.

And then we've also got things like the costs of the criminal justice system for those people who might be in the criminal justice system and have a traumatic brain injury, which may have increased their predisposition to be incarcerated in some way. And then also we've got a breakdown of the cost of the education element as well. So within the data, we've got age groups data as well. So we can identify the children and estimate the cost to special educational needs as well. So, it's broken out into lots of those different areas. Around about half of the cost, half of that 43 billion, is in NHS direct spending and local authority costs in terms of social care costs as well. So the other kind of half is made up of mainly lost productivity, which is about 21 billion. And then about a billion and a half of that education and criminal justice spend as well. |

| James (6:44) | Yeah, so there's some clearly direct costs, how much it costs to put someone in hospital, how much are they going to social care? And we know that that system's a whole load of other stuff we can talk about in the way that brain injury survivors go through that transition from health to social care. And then there are those sort of more indirect costs you talked about, about people can't go back to work, so they're not generating revenue, they're not paying taxes into the system.

So can we save some of this money, I guess, is the next question. Maybe Chloë, you've got some thoughts about that as well. If it's costing us all of this money, can we save any of that? Can we recoup some of those costs? |

| Chloë (7:21) | I think that's the hope, isn't it? That we look at this data to sort of, you know, try to provide an estimate, and then the next step is to sort of say, well, actually, how can we, you know, take some of these costs away? So one of the kind of estimated costs that we have in here is carers' costs. And we know that when we provide or when people have access to specialist neurorehabilitation, that the amount of care they need is actually significantly less. That they have a much better chance of returning to work or to education settings.

We know that they're less likely to be incarcerated if, you know, for example, if they're a child who's had a brain injury and they are supported at that stage, they're much less likely to go into that system. So there's a whole raft of savings that can be made across the board. And I think one of the things that we wanted to do with this report was to really demonstrate how those savings can be made. And there's probably a second piece of work that will evidence that more strongly, but it's really to kind of give ourselves this sort of line in the sand of saying, this is where we are. We know that we can do better. We know that we need better access to rehab and better support for people with brain injuries and their carers. And the long-term effect of that will be, not just that those people will have a significantly better quality of life, but actually that we will save the public person a lot of money. |

| James (8:47) | Yeah, sounds good. Jennifer, Chloë mentioned the carer costs. We know that across the UK, there are tens of thousands of unpaid carers, it's people, parents and family. How do you kind of cost that? Do we say that they can't work and we count that what they would have earned? How do you get those sums? |

| Jennifer (9:05) | So we've made some assumptions there based on some surveys of carers and who they're caring for, and what conditions the patients might have, and how long they spend out of the labour market. So it's made up of a combination of factors, really. The main one being the loss of productivity by them not being in paid work. We are obviously also accounting for formal social care, which accrues to many to local authorities. But I mean, the carers' cost, it's probably conservative because we've taken quite conservative assumptions on how many carers and what kind of numbers of caring hours per week and things like that. But it's around the £5 billion mark, which is a massive spend, which people, you know, we would otherwise have to pay for through some kind of social, formal social care.

So yeah, £5 billion annually is a significant amount of money. |

| James (10:01) | And I guess if we didn't have one of these unpaid family members doing this caring work, we'd be paying twice that. |

| Jennifer (10:09) | Probably an awful lot more. Yes, exactly. And we've had to take assumptions about, you know, the jobs that they would be in and the average wages and things like that.And assume that they're kind of a similar age demographic to the person they're caring for and things like that. It probably evens out a little bit in the wash.

But yeah, it's one of these areas actually where, in doing this report and doing this work, we found an awful lot of data gaps, really, and data that's missing. So carers is one area I'd really like to see better evidenced, really. A lot of the carers' surveys are really useful in terms of things like hours of care spent or other things foregone whilst people are caring. But they don't always attribute it to the condition that the patient has. So, for example, there's some surveys of people with cancer and their carers where you can obviously attribute the caring cost to that condition and in terms of the cancer they have. But in terms of acquired brain injury, there's not quite as much recording and not quite as much data gathered, really, on the condition that the patient has. So we do have to make quite a few assumptions on that. |

| James (11:22) | Yeah, and I guess some of that is just because acquired brain injuries are so different. People's outcomes are enormously varied. (Jennifer: It's complicated, yeah.) It would be really quite different. So what about benefits? Do the benefits that we pay to people because they're injured they can't work, do they count in this economic review, or how do they fit? |

| Jennifer (11:44) | Yeah, so they sit alongside the economic costs. So when economists talk about DWP types of benefits and spending on incapacity benefits and things like that, it's classed as a transfer because it's a transfer from tax into benefit rather than a cost in the economy. So we did manage to calculate that, and I think that's quite a conservative cost as well. So we've come out with £1.9 billion per year. And that's in, as I said, incapacity benefit, things like PIP, attendance allowance for carers as well, and some of those health components of universal credit and things like that. So that's just the DWP kind of benefit spend that we can attribute to acquired brain injury patients.

And again, some of that data it's quite hard to proportion it out into the conditions. So we've had to make assumptions there. So it might be on the conservative side, really. All of these, we've taken kind of conservative assumptions. So it's around about, yeah, £2 billion per year, which again is a massive, massive amount. |

| James (12:48) | Huge amount of money, isn't it? And also, of course, without wishing to double count stuff, if we get people back into work, they're not claiming that and they're paying taxes. We need to think things through, don't we? Chloë, you mentioned two sorts of areas of particular focus where brain injury is a real problem in the criminal justice system and the education system. We know that, what, somewhere between 60% and everybody in prison has some sort of history of brain injury, huge numbers. And in education, we know that people have really sort of long-term issues getting back into education after brain injury.

Are there things happening sort of in the brain injury field to help smooth out? Because it's not just that we say, well, don't send them to prison then. That's clearly not going to work, is it, but what we can try to do is stop people going back into prison after brain injury. |

| Chloë (13:37) | Yeah. So I think that the first thing to say is that brain injury affects people in all areas of life. And you know that what we are doing is really just a very small part of the different areas that need to be addressed. So just to give you some examples of things that have hardly been touched on, acquired brain injury amongst people who are homeless, acquired brain injury amongst veterans, and there's a bit of crossover amongst those two areas that need much, much more focus. We've chosen to kind of take our work into these sorts of three or four main areas, health and social care being one. Education being another, because we know that when children have brain injuries, if they are not severe, very often they'll go back into the education system, into the mainstream education system. So once they are there, educators (so that's teachers, but also teaching assistants, special educational needs coordinators) really know very little about brain injury. It's not something that's taught in any of their sort of teaching modules. It's something that is quite invisible.

So a child who goes back into school quite often won't have any kind of visible effects of the brain injury. If they've had the injury, particularly in primary education, it's not something that will be really sort of obvious. So sometimes their needs kind of emerge later on, by which time sometimes that brain injury will be forgotten. So we are doing some significant work in this area to try to, firstly, make sure that those people who are educating them can support them adequately, because they have the capability to do it, they just don't know what they don't know. We also want to make sure that those children are counted, because it's another area where data is really thin on the ground. So within schools, they have a census where they count children, they put them into different categories depending on what their sort of needs are, and there isn't one for acquired brain injury. So they tend to be sort of put into the various other categories, which means that they're kind of scattered, and nobody really has an idea of how many children are in the system that need this kind of support. There are kind of multiple ways that those children need to be supported, and I don't think any of those are particularly gigantic cost-wise, but they're things that would make a really, really huge difference. |

| James (15:58) | It seems to me that what you've been describing there, in terms of that kind of extra support, that costs money, doesn't it? So Jennifer, how does it work about saving money and spending money, right? We want to do things to get people back into work, we want to get kids supported in school. Presumably, that costs more than the figures we've got at the moment, because we're not doing it and we're spending loads. |

| Jennifer (16:22) | Yeah, I mean, I think there are certainly preventative spending measures, which would cost more in the short term, but in the long term, we would see massive savings from. So when I was doing this work, looking through the evidence as well, we found that the benefit-cost ratio for long-term neuro-rehab, for example, is 16 to 1. So for every pound spent, and this is in the NCR economic business case as well, for every pound spent, you can expect in the long term, 16 pounds of benefit savings. So, you know, there is a case there to be made, I think, for spending more money up front and saving more in the future. |

| James (17:10) | Yeah, it seems crazy that we haven't done that already. And I guess maybe one of the reasons we haven't done that is because we don't know how long that long term is. Do we have any idea how long it would take to recover? |

| Jennifer (17:21) | I don't think it's, it's not a massive amount of time. I'm trying to think of the time horizon for the National Centre for Rehab's work. I think it was around about 20 to 30 years. You're looking at, unfortunately, a lot longer cycle than a spending review or a parliamentary term, etc., which obviously adds to the complications. But, you know, it's not a massively long duration. And for lots of different government policy areas, especially in health, you'd be looking at 20 to 30 years to recoup savings anyway. |

| James (17:59) | Yeah, so these things do happen. I guess when you're having five prime ministers in a week, it's quite hard for them to start thinking longer term. And I guess, Chloë, what we want to do with this report is to get the focus on that and to think, look, we need to invest now to save in the long term. And not just to save the money that we've been talking about, but to save the quality of life of tens of thousands of people across the country. |

| Chloë (18:21) | Yeah, absolutely. And, you know, when we were talking about those children and young people, you know, it's not just this sort of link to the justice system. It's enabling those children to better perform in order that they will, you know, lead a kind of more fulfilling life, that they will be able to enter a career and work that's fulfilling and have a kind of family life that's fulfilling as well. So it's not just about that sort of prevention, but it's about developing a better society, isn't it? Because we know that these numbers are actually really big. We're not talking about one or two people, we're talking about enormous numbers of people. And, you know, that's another area that we're really hoping we will be able to develop more accuracy over, because I think Jennifer said lots of the sort of estimates have been very conservative. And lots of the data that we've, the published data that we've looked at, is not particularly current and needs to be updated and needs to be more accurate. So there's definitely big gaps there and things that we want to sort of pursue as time goes on. |

| James (19:22) | So, are there then some key recommendations that come out of this report? What do we want to happen as a result of getting this thing out there and kind of spread around? And if one's going to write letters to their MPs, what are they going to tell them to do? |

| Chloë (19:36) | I think that one of the things that we really would like to see alongside many other organisations is a sort of statutory right to rehabilitation. We know that it's not something that everybody is able to access, whether it's due to kind of lack of services in the particular area that they live in. Whether it's the particular service that's, you know, a lack of workforce, those types of things. So we really feel that specialist neurorehabilitation for acquired brain injury should be in place, wherever you live. And that there should be a properly designated system whereby when you are discharged from acute care, that you go into a sort of specific pathway that dictates what type of care you will get, and that extends into the community and that your carers and family members are also considered within that. But obviously that needs some funding, so it's really about the government sort of coming up with a funding mechanism or the ICBs coming up with a funding mechanism. The other things that we have asked for are better data and better use of that data. We really want to make sure that the data is collected properly and that it's interpreted and utilised properly as well. |

| James (20:42) | Yeah, and I guess ministers look at this and they're terrified and say we can't possibly do anything about that. Don't believe it. Well, there's the challenge, right? Prove it to yourself. Prove us wrong by doing the proper count yourself and collect that information, see what figure you come up with. |

| Chloë (20:57) | That's right. And obviously data is a central part of wider government planning. It's something that is being reviewed within the sort of 10-year plan. So we hope that acquired brain injury will fit into that, but will be something that is looked at specifically and not be lumped in with lots of other things as part of a generic kind of data exercise. |

| James (21:18) | There's also this thing that I've heard it being called “the left shift”, but it's about shifting from hospital to community care. It's about moving from analogue to digital stuff. And that's something that HealthTech Research Centre are really quite heavily involved in. So are there cost savings just in the way that we deliver rehab as well as just making sure that everybody can have access to it? |

| Chloë (21:40) | Yeah, I think so. I mean, I think that community rehabilitation has got huge potential to help people with acquired brain injuries. There's a lot that can be done within the community. And obviously it really helps people, particularly children, who you don't really want to sort of lift them up out of their home environment and their kind of community setting to have rehabilitation as an inpatient. It's much more beneficial to be within your home environment.

And within the private sector, there's a massive amount of community rehab that's brought in. So, whether it's sort of private occupational therapy, physio, the whole team can go into the patient's home to kind of deliver what's needed. Obviously, there's always going to be a certain amount of acute neuro rehabilitation that you're going to need to be within a kind of inpatient setting for, but a huge amount can be done in the community. And I think building those community teams is something that is much needed. There's a real workforce issue there at the moment. |

| James (22:40) | Jennifer, do you think we could save some of those direct costs just by changing the way that we deliver the services? Is that something you can kind of look at in the data at the moment? So when it costs this much for a hospital bed, it'd be cheaper if they weren't in that hospital bed and we could deliver it. |

| Jennifer (22:55) | Yeah, definitely. I mean, we've got in there £5.2 billion of NHS acute care, and that's very much based on hospital episodes. And if we could reduce those and just improve that pathway, really to better rehab, we'd see some of those other costs come down as well. And I think also one of the areas we've not really talked about that we looked at in the report was, for the first time, we've actually costed the wellbeing costs to both patients, carers, and their families as well. And they're really substantial. They're nearly double the cost of the economic costs on an annual basis.

And that wellbeing cost in terms of quality of life impact of not just that patient, but their partners, potentially your widows, children, carers, then if we could improve the pathway to support and to care, we could save a lot there in terms of that wellbeing cost as well. |

| James (24:02) | Yeah, it sort of reflects that huge impact that doesn't just happen to the person who has the injury, does it? There's a circle of community and people around those as well. So, we are recording this podcast in June 2025. The report was published about a month ago. What's happened since it was published? |

| Chloë (24:22) | On publication of the report, we had a meeting in parliament and we invited MPs and peers and people from various different departments to come and talk to us about the new report. We sent copies to ministers, one of whom was Ashley Dalton. We sent a copy of the report to her, and she's the Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Public Health and Prevention. And the previous government had agreed to publish an acquired brain injury strategy back in 2021. And we'd spent quite a lot of time with the then government trying to develop a strategy. So the new minister has had a look at that, and we've been liaising with them over whether they plan to take that forward.

So on the 14th of June, just a couple of days ago, we at UKABIF have received a letter from the minister to say that they recognise the impact the brain injuries have on individuals and their loved ones and that they will be publishing an action plan in the autumn. So they've moved away from this idea of it being a strategy. They want it to be very kind of action-focused, and it will really be something that kind of sits alongside the forthcoming 10-year health plan, which obviously is going to be the overarching plan for the future of the NHS. And so the action plan for acquired brain injury would then focus on specific actions and deliverables for acquired brain injury against the backdrop of the 10-year plan. So although we don't have too much detail about what is going to be within the plan at the moment, it feels like a very kind of positive response to the report, which we're really, really pleased to see. And it's obviously something that we wanted to move forward with. So, a positive outcome. |

| James (26:06) | Yeah, that's encouraging noises, isn't it? We know that governments can change and pandemics can come, and the world can change in an instant, but all we can do, I guess, is keep pushing forward and hope that we start to see some results. We see some of these savings, these enormous costs, but also we give people the services and rehab that they really need to move forward. So thanks ever so much, Chloë and Jennifer, for joining me on the podcast. I really appreciate you giving your time and telling us about this really important project. We will put links under this podcast to the UK Cost report and to the Time for Change report that Chloë mentioned earlier on as well. Have a read of them and digest.

Thank you very much. |

More like this:

Research Podcast – Matthew Colbeck

Listen to James Piercy talk with researcher Matthew Colbeck Matthew's work explores the ways that coma and [...]

Headway webinars

Headway is running a series of webinars that are free and open to all! Anyone can sign [...]

Cambridge Science Festival 2025

Join us at the Cambridge Science Festival, 11:00am-4:00pm on Saturday 22 March. We are running a drop-in [...]