>

| James (0:10) | You are listening to another podcast from the HealthTech Research Centre in Brain and Spinal Injury, where I've been chatting to researchers and innovators and patients and carers about their understanding and experience in the world of brain injuries. And today, I'm joined by Antoniya. Antoniya, you're an interesting person to have on the podcast because you're not a patient, you're not a doctor, you are, dare I say it, a mathematician.Is that right? |

| Antoniya (0:39) | Yes, that's correct. Thank you very much for having me. |

| James (0:42) | So that's kind of interesting, I think, that actually your background is in maths, computer science, but you're doing some work now, which is really about medicine. It's about biology, really, and those kinds of improvements. I wonder if you could just tell us a little bit about how you ended up in this field. |

| Antoniya (0:5) | Yeah, thank you for asking me this. So I grew up in Bulgaria, actually, in Eastern Europe, and I studied mathematics, applied mathematics, in Bulgaria and in Germany. I was very passionate about mathematical equations, actually, and theory.But I ended up doing a PhD in the UK in computer science and AI. This was very much about programming and analysing data. And so, funnily enough, I had an offer from Sheffield University to model brain activity, which I was quite excited about.

But I ended up in Oxford as a very young postdoc, age 25, freshly out of that PhD in AI, embedded in the hospital. So my interview was in the hospital. He had a big hospital in Oxford, John Radcliffe, with a very well-known professor, Professor Chris Redman, and a team. And I was just in awe. I entered, you know, where delivery ward is, and I was like, oh my god, I want to be here. So I think I just fell in love with the concept of doing something very clinical. And obviously, the topic was, from the onset, was about analysing data about babies during labour, before they are born. So I just fell in love with the topic directly, age 25, had no babies at that time, knew nothing about the challenges in that field. I thought it would be easy. |

| James (2:17) | Yeah, that's fascinating. And I'm going to use the big important word there, data. And there's huge amounts of information collected, isn't there?If we just think about your particular case, where we're monitoring babies in the womb and developing, we're collecting information all the time. And I guess what you're trying to do is, how do we make sense of that information? So we use it rather than just churn it out. |

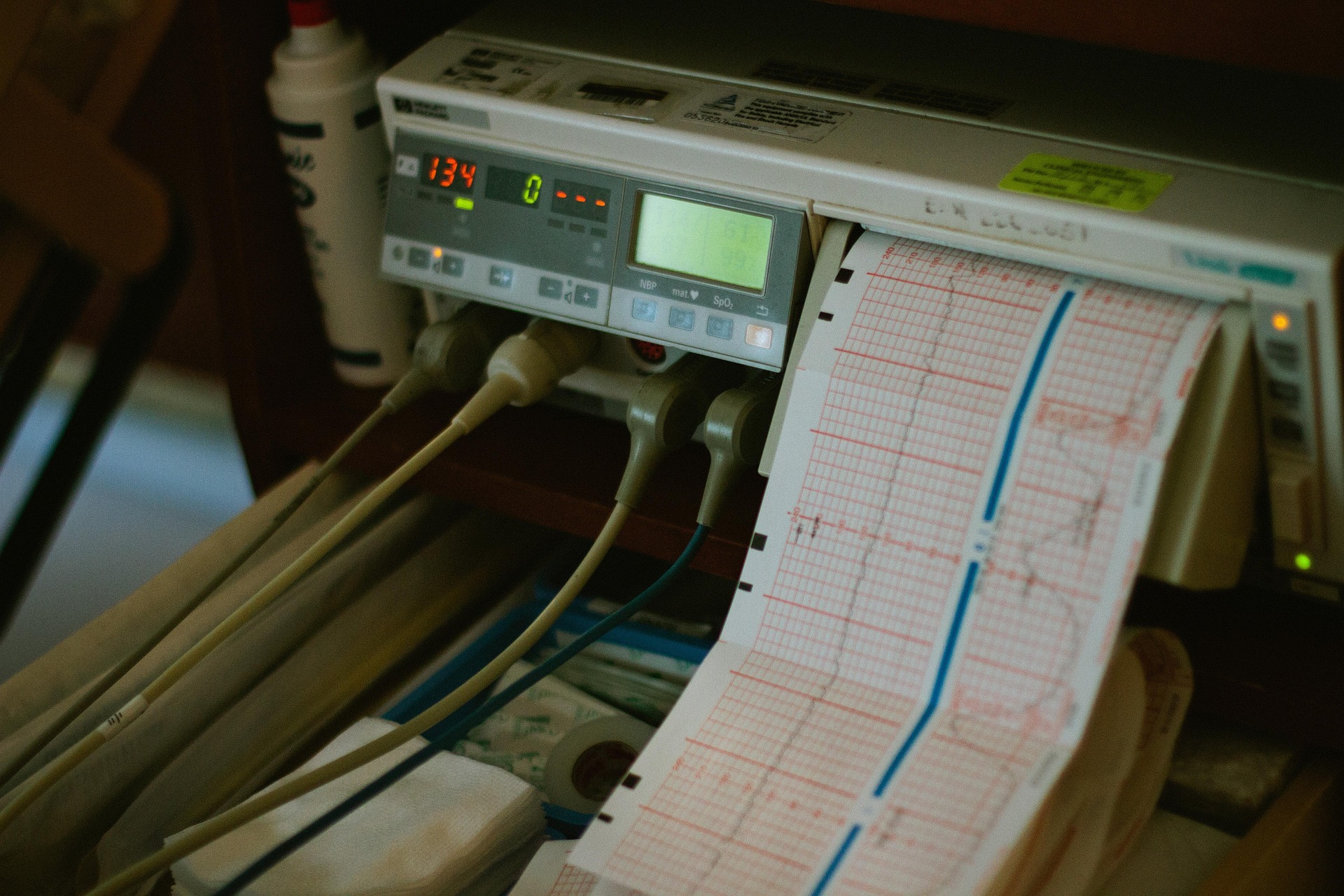

| Antoniya (2:41) | Exactly. And I must admit, definitely, I've stepped on the shoulders of giants, and in particular, Professor Redmond, who some of your listeners may have heard about. He sadly passed away last summer at the age of 83.So he actually had that vision long ago, he was a physician. He was caring in the 70s and in the 80s for women with preeclampsia here at John Ratcliffe Hospital. And he had that vision of, especially as foetal monitors were invented.

So these are these kind of belts that we put around the maternal abdomen, and they continuously provide a heart rate of the baby alongside a few other parameters, but the heart rate is what really matters. And that's, yes, that's a lot of data points. This can be done for many hours during labour or during pregnancy. And it's actually multiple measurements per second, it's four per second is the original data that I have. So yes, over a couple of hours, or 10 hours, that's quite a lot of data points. But this heart rate monitoring, it's really valuable in the context of characteristics about the mother as well, like, for example, how many weeks pregnant she is. Does she have any comorbidities, preeclampsia or diabetes or any other concerns about that pregnancy? There are other things like if the mother is running a temperature that would affect that heart rate of the baby and so on. So you never really analyse the heart rate of the baby on its own. And what really matters as well is the variety of different outcomes. Here we have in principle two people, we care for a mother and the baby. And then there's so many different outcomes that we care about. And we all want healthy baby, obviously. But then if baby is born in a condition that it's not too bad, or not too good, or there's subtle things, or one or two things, we don't always know what that means about the pregnancy or the labour process and what caused any issues. So to summarise what Chris Redmond had the vision actually was to start collecting that data with computers already in the early 90s when no one was talking about AI or big data and so on. So this was the first very important thing he did. He started collecting it in digital format systematically, all the routinely monitored women, and he set out to prevent mothers and babies dying from preeclampsia in the mother. And he largely succeeded in many different ways to achieve that in his lifetime. But the data for labour monitoring, that's where I come in, he just systematically collected, collected, collected, not only the heart rate, but all of this bigger picture and what happens to the baby and the outcomes. And when he hired me, and then the second very bright thing he did is obviously to hire me. So he hired me freshly out of that PhD with no experience in maternity whatsoever. And he trained me in the concepts and he tossed all that data at me. And he said, deal with it. And I must say the data was horrendous, right? It was really messy. And I kept on thinking the whole first year, my God, he was really lucky to get a good programmer like me, I can programme very well, codes. But if it was someone else who can analyse data, but cannot programme like I did would have been drowned in that data. But yeah, so it was in reality, his vision, I was naive, young, I was under his wing, and I was just asking all these questions and just analysing and getting the data in shape initially. And then I started analysing him and I thought he would have the answers and I would just kind of programme things and kind of make them modern and computerised. But I thought the clinical knowledge is there. And when in year two and year three, we started having continuous conversations in which I asked questions and he tells me I don't know. That was not great. With time, I found out that not only he didn't know, nobody in the world knows. And that's why I stayed. The questions kept coming, the clinical questions kept coming. In reality, our technologies are extremely limited in our field. We still are in the infancy of knowing how to assess risk for the baby in pregnancy, especially around labour. So here I am, 18 years later, still with that problem. It's horrible. Still posing this kind of questions. How do we use that data best? How do we provide solutions in the clinic that can help doctors and mothers really triage, if you wish, babies who needs to be delivered more quickly and with medical help or who is actually absolutely fine? And we need to kind of ease off and let nature take its course. So that continues to be the number one question. |

| James (7:18) | So I guess I guess the power of AI machine learning is this is that you learn to recognise patterns. So it's not like we're just going to take the temperature of one person and think, oh, that means X, Y, Z. But actually, what we're trying to look for is a pattern that's developing over time that we've seen before.And we recognise, well, the last time this happened in a large number of women, we had a negative outcome. So we need to intervene to stop that happening. Exactly, exactly. |

| Antoniya (7:45) | Very well said. And there are a couple of elements to it. Heart rate on its own for the foetus over many hours during labour or in shorter segments at onset of labour before.It's complex graph on its own. So there is potential benefit of having a computer read that graph for you, even just to measure elements, right? So even without that concept of like, oh, is that similar to a prior pattern?

Is that bad or good pattern? Even before you ask that question, your ability to not look by eye at this complex graph, how is a midwife supposed to look at that complex graph while she's caring for the woman and caring for making notes and bringing it is just unfair and stupid. There should have been always a computer reading and measuring, measuring the heartbeats, all the parameters we care about. So there is first an element of measurement. And I think Chris Redmond set out initially, really to do that measure. At least it's objective, because at the moment with heart rate, when midwives and doctors look at it, they have, one will tell you, oh, that's five. And the other one will tell you it's a four. And that is all. And then the same midwife, that's so well tested, will come in, let's say, five days later. And if you show the same heart rate, we'll say, oh, it's a four. So that disagreement is very well understood in a complex, complex graph. So number one is being able to measure a given objective metric. So if one says is five, it's five in this hospital, it's five in the next hospital. |

| James (9:12) | Yeah, exactly. |

| Antoniya (9:1) | So that objectivity is extremely important. If you can bring that in clinical care, you're actually able to start collecting data in a way as well that you can analyse it because it's objective. Because if it's everybody's opinion, then you can't even analyse and learn from it very well.But then the second thing is what you tapped in is, yes, once you've collected data, I mean, my data set that I actively work with starts in 1993. We have now been able to analyse and kind of distil in the memory of the computer the data from over 75,000 prior births in our domain from Oxford on its own. And then we now have been generously been able to start analysing data in other centres in UK and abroad.

That's quite important that you don't sit just in one hospital. And now when you have this kind of data sets, you can start, yes, learning patterns from them. And what a very important thing is what you can provide is this kind of what we call sent out charts. You can provide a population measure of what is normal and what are the extreme ends and who can be richer. And then once you measure things, even that is already an invention. Without doing any fancy AI, even if you are able to say what is normal for a population and then have your measurement put on that scale, that's already giving you information clinicians have never had before. Is that very high risk? Is that very low risk? Is that on extremes? Your baby might still be well because you're only risk assessing, you're not able to diagnose with our tools. So even if you're an extreme end, your baby might still be fine. But at least you can have that informed discussion that you are in potentially higher risk and why. |

| James (10:50 ) | Yeah, and closer observation, I guess. You touched on something there that I wanted to bring up about inclusion, because, you know, large numbers of births. But if out of those 75,000 births, 98% of them are white women.We don't have great information. One of the problems with machine learning systems is that they have a bias because they only learn from the information we're given. So do we know, are there differences between ages of women, between ethnicities of women, and how do we make sure that we incorporate that range of data into the set?

Yeah. |

| Antoniya (11:27) | Can I unpack that? Because that's quite a few things in that question. And this is a very common question at the moment that people ask.It's a very good one. I want to say one thing, the size of numbers, in particularly a field like ours, where majority, majority, majority, 99% of babies will be well, and will not sustain brain injury, thanks to all the clinical care that we have. So in our case, the size of databases, it's actually really important because compromises are very, very rare.

And they are very heterogeneous, you know, babies are very different. There are different ways in which they get brain injured in labour. So you actually really need to treat this kind of cases as gold in a sense of important ones that each one of them, your computer and yourself can learn from. Right. So that's important. The second important thing is that yes, in AI in particular, yes, the data sets can be quite biassed. In our case, it's very important to understand that clinical care keeps changing as well over, we are looking at 30 years of data. It's very, very interesting, you learn a lot. And you can see, for example, how clinical care has been changing. But also like in a sense, there are more caesarean sections, for example, there is a lot of more babies that are now caught out earlier through the system due to very good ultrasound scanning, they have been flagged as high risk earlier, they're not allowed to end up in our case, labouring for hours, right? And that reduces the risks. But also populations have been changing, women are now different than 30 years ago, babies are larger than they were 30 years ago. So being able to adjust to this, these are tangible risk factors, right? A bigger baby size wise, it's as far as the labour hearing process is concerned, it's not always a diabetic mother, it's not always the best scenario for labour. So these things change. But on top of that, so you mentioned ethnicity, obviously, we are now very, very good at measuring outcomes and monitoring what happens in this country. But also in other countries, people are doing that. Here, we have been extremely good, thanks to Embrace and other initiatives. We know that there are serious discrepancies in outcomes for mothers and for babies. Now, in our team, the research focusses on babies in particular, not that mothers are not important, it's just there is a lot of other research about the mother. And we can only focus on one thing, to be honest. So what we try to do is prevent the baby from harm in labour and as a mission of the team. So in that kind of sense, yes, there are some discrepancies between ethnicities. However, there is likely biological reasons for some of them. But as far as the heart rate is concerned, which is one of the main focus of what we do, there hasn't been, and we keep an eye, you know, there hasn't been an active biological evidence that the heart rates are different according to your race. We keep an eye and then you should adjust to that. But what we don't want to be doing is now using the data to say that it's high, for example, that certain populations are at higher risk just because they are higher risk for other reasons, right? We need to be looking at the biological reasons. Does that make any sense? It's an interesting topic, to be honest, and we're looking with interest. In our data set, of course, in Oxford, we have quite a lot of biases in terms of population. And we are working closely with Birmingham, for example, where it's so close to Oxford, it's just an hour with the train if it's on time, but the population is very different. So we are in the process of analysing that data and we're looking with interest, scrutinising closely, are there any differences of the methods we have for those? But because we have focused on physiological metrics that matter, I don't personally anticipate that our algorithms are in any way biassed in this kind of way, but we'll keep a close eye. |

| James (15:25) | And I guess that's the point, right? We note this stuff and we record these things, and if they turn out to be irrelevant, it doesn't matter, we haven't wasted any effort. But if we do see some kind of difference, we need to be aware of that to factor it in as we go forwards.So in terms of this group and these podcasts, we're talking specifically about brain injury. And obviously, some babies are at risk of brain injury during the birthing process and sometimes a bit before that. Do we know what causes those brain injuries?

Are there sort of common reasons that that might happen in babies? |

| Antoniya (15:59) | Yeah, I'm not a clinician myself, but I have had the privilege over the years to train closely with giants like Chris Redmond and quite a few others, including the Foetal Physiology Lab in Auckland, that does a lot of experimental work with animals to try to answer the brilliant question you're asking. There are good understanding of some of the pathways and the ways that brain injury in the foetus happens. But because the foetus is in neutral, right, we are still so limited in the technologies and the tools for us to, that's the whole challenge in our field.So as a scientist that believes in data and looks at data, I would tell you that the jury is in many ways out. In our topic, it's specifically very litigious as well. And then in particular in US, it's very convenient sometimes for experts to look at a case once it's happened.

And with hindsight, then look and say, oh, this is a problem, this happened in labour, these are the causes. But the reality is it's extremely difficult to actually have a certainty of what, how, went wrong, where. The common pathways, the common understanding is that there is lack of oxygen due to contractions, due to the placenta being challenged, right, the cord being trapped, the baby descending through the canal. And that process sometimes, if there is not enough breaks between the contractions, that can be the actual cause, lack of oxygen. But what is more interesting for me and where I focused a lot of where the data has taken me over the years is that actually a healthy baby with a healthy placenta, it's going to sustain a lot of that normal labour process without any issues, right? It will defend itself. It has extraordinarily good mechanisms to defend itself against that lack of oxygen. It's extraordinary. It's fascinating. And that's what kept me in the field. However, the babies that arrive at the onset of labour with some kind of vulnerability from before, and that's where I'm focussing my team and our efforts in the past five years. I think that's the low-hanging fruit. These babies are just not going to have the capacity to sustain many hours. They'll be fine with some time. And actually being able to diagnose and kind of detect these babies or risk assess them so that they are monitored more closely. And then as soon as it's becoming too much, we have a lower threshold for intervention for those. I think we should be able to shift the needle definitely in the right direction. |

| James (18:2) | Do you see changes happening soon? Will we start to see better monitoring and better predictions of risk, even just in a few years' time? We're not going to answer all the questions, but are we going to enable doctors to make those interventions sooner and more appropriately for mothers and babies? |

| Antoniya (18:45) | I really want to say yes. So I work day and night personally and my team, I try to have them work day and night as much as I can. So we as a team work tirelessly to have, for example, in the clinic, SAP hopefully next year in Oxford first, a tool to provide that early risk assessment that I'm talking about.That's our focus has gone into a lot in the past years, to have it conveniently, seamlessly in the clinic, in the hospital where midwives can click a button and have the information easily in a fast-paced environment and make their understanding of the risks for each woman at the onset of labour, at triage already, so that we can bring the right care to the right woman basically very early on, as soon as she's in the hospital with anticipated labour.

So I personally really hope that the work that we are doing is going to make a tangible change. It's not going to suddenly save all the babies that we need to save so quickly, but if we can do, our projections showed that probably about a third of babies that at the moment sustain injury at term in the UK should be preventable with a better risk assessment like this. All the other reports that have been studying these kind of things showed that about half of them are preventable with the right knowledge and the right risk assessment and our internal data and external validation, which is under review at the moment, so hopefully will be published out and I'll be able to say more about it, is showing that about a third of babies with our tool we should be able to, and we should be able to reassure, on the other hand, quite a few women that actually, look, the risks are low here, we don't probably need to be over-intervening, because what will be happening at the moment in this country and abroad as well is that there is a lot of over-intervention, because we are scared. Of course we are scared, understandably. So that's my hope as far as our team is concerned. On the other hand, as an academic and as a person with a broader view, in my lifetime what I want to see is better technologies, not just software that is attaching to the current technologies with a click, which is what we focused on, because it's the quicker and easier solution, you know, if we can prevent a third that's invaluable, I'll go for it, but what I want to see is new monitors, new technology that is able to give you a glimpse inside in the uterus, in the blood flow of that baby, in the blood pressure of that baby, give you other vital signs, because we are very limited with a heart rate, and I've personally worked for a few years and continue to collaborate on brand new sensors in that domain. I was fortunate enough to be part of a large programme funded by a welcome leap, a code in utero, that was just completed after three years and gave 50 million dollars into trying to accelerate that research, and there will be more outputs coming out of that programme. I would hope that we'll see in my lifetime better technologies, better technology can tell us more, and there are quite exciting few bits happening around the globe, including in the UK. |

| James (21:47) | Yeah, that's great, and obviously we are the Health Tech Research Centre, all about that tech, and some of it is practical, physical bits of kit, and some of it is code and maths to kind of bring us back to where we started from. Well, Antonio, thank you ever so much for finding the time to have a bit of chat and talking a bit more about your work, and we look forward to hearing some more results as things develop over time. |

| Antoniya (22:10) | Yeah, thank you very much, pleasure to be here. |

| James (22:12) | You've been listening to a podcast from the Health Tech Research Centre in Brain Injury. Check out more episodes in this series, like, subscribe, do those things that people do when they're interested. Thanks very much. |

More like this:

Charity Podcast – Juliet Bouverie

James Piercy talks to Juliet Bouverie CEO of the Stroke Association. They discuss the importance early recognition [...]

Patient Involvement Podcast – Gillian

Listen to James Piercy talk with Gillian, a member of our Public Oversight Committee, who is a [...]

Patient Involvement Podcast – Kavita Basi

Listen to James Piercy talk with Kavita Basi, VP, Author, Speaker, podcaster and Ambassador. Kavita faced a [...]